کار عملی با نقشه های دریایی

منبع : حمل و نقل دریایی

کار عملی با نقشه های

دریایی

Plotting and piloting

Home Nav.

course Sailing Greece

Turkish Coasts

Yacht

charter Gulets

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Lines of position

The modern chart shows us positions of many recognizable

aids to

navigation

like churches and lighthouses, which facilitate the approach to a

coastal area. This concept originated from a chart by Waghenaer![]() and proved a milestone in the development of European

cartography. This work was called “Spieghel der Zeevaerdt”

and proved a milestone in the development of European

cartography. This work was called “Spieghel der Zeevaerdt”![]() and included coastal profiles and tidal information much like the

modern chart. It enables us to find the angle between the North and for

example an offshore platform, as seen from our position.

and included coastal profiles and tidal information much like the

modern chart. It enables us to find the angle between the North and for

example an offshore platform, as seen from our position.

Compass courses |

True courses |

Taking a bearing on this oil rig with a compass provides

us with a compass course. This course first needs correction for both

variation and - via ship's heading - deviation![]() before plotting a Line

of Position (LOP) in the chart as a true course.

before plotting a Line

of Position (LOP) in the chart as a true course.

Our

position is somewhere along this line.

Ranges

A precise way to obtain a LOP, and without a compass, is to locate two

aids to navigation in line. The map of Laura Island on the right shows

four examples of ranges, each

consisting of two aids to navigation.

A precise way to obtain a LOP, and without a compass, is to locate two

aids to navigation in line. The map of Laura Island on the right shows

four examples of ranges, each

consisting of two aids to navigation.

Please, note that:

More distance between the two landmarks enhances accuracy.

And less distance between the vessel and the closest aid to navigation also enhances accuracy.

One of these four ranges consists of two lights that are

intentionally placed to provide a LOP. These pairs of lights are called

range lights or leading lights.

In this case they indicate the approach towards the marina and mark the

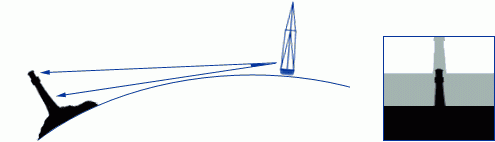

channel between the dangerous rocks along a true course of 50°![]() . When looking towards any leading lights, the nearest one

will be lower

. When looking towards any leading lights, the nearest one

will be lower![]() .

.  Therefore, in the middle of the channel both lights will

appear vertically above each other.

Therefore, in the middle of the channel both lights will

appear vertically above each other.

Even when there are no man-made structures available, a

range can be found by using natural features such as coastlines and

islets. The example on the left shows a yacht that will avoid the

dangerous wreck as long as the islets don't overlap.

Position fix

If two LOPs intersect we can construct a position fix: the ship's position on the

earth.

Often

however, a triangle occurs when a third LOP is added in the

construction. This indicates that there are errors involved in at least

one of the bearings taken. In practice, we should consider each LOP as

the average bearing in a wider sector of for instance 10°![]() .

.

|

|

|

The optimum angular spread is 90° (two objects) or 120° (three objects). Moreover, bearings on distant objects bring about more uncertainty in our position fix as the sector widens. Finally, if moving fast you should not put any time between the bearings.

The next example features a nocturnal landfall on

Willemsen Island - you are welcome to visit, but mind the rocks. The

position fix is plotted by taking bearings at two light-vessels as their

lights appear over the horizon![]() . The variation is -1° and the ship's compass heading is

190°. Since we use our steering compass

. The variation is -1° and the ship's compass heading is

190°. Since we use our steering compass![]() for our bearings, we can use the same deviation table.

That means a deviation of -4° with which we can calculate (cc + var + dev = tc)

the true courses.

for our bearings, we can use the same deviation table.

That means a deviation of -4° with which we can calculate (cc + var + dev = tc)

the true courses.

Construction

|

|

Without a third LOP - forming the dreaded triangle - there is the false suggestion of accuracy. Yet, instrument errors, erroneous identification of an aid to navigation, sloppy plotting, etc. can and will cause navigation errors. Therefore, if close to e.g. rocks, you should assume to be at the worst possible position (i.e. closest to the navigational hazard).

The lines plotted in the chart are always true courses and these are labeled with true courses by default; the “T” is optional. If labeled with the corresponding magnetic course or compass course add an “M” or “C”, respectively.

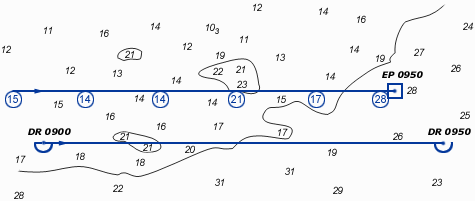

Estimated position

It is sometimes impossible to obtain more than one LOP at a time. To determine the ship's position with one aid to navigation we can use a running fix. However if a running fix is not possible, we can determine an estimated position.

An estimated position is based upon whatever incomplete navigational

information is available, such as a single LOP, a series of depth

measurements correlated to charted depths, or a visual observation of

the surroundings.

An estimated position is based upon whatever incomplete navigational

information is available, such as a single LOP, a series of depth

measurements correlated to charted depths, or a visual observation of

the surroundings.

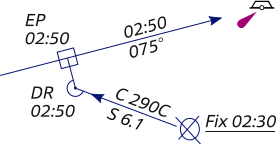

In the example on the right we see an estimated position

constructed using a single LOP and the ship's dead

reckoning position (DR)![]() .

This is done by drawing a line from the DR position at the time of the

LOP perpendicular to the LOP. An EP is denoted by a square instead of an

ellipse.

.

This is done by drawing a line from the DR position at the time of the

LOP perpendicular to the LOP. An EP is denoted by a square instead of an

ellipse.

Do not rely on an EP as much as a fix. The scale of reliability, from best to worst:

Fix

Running fix

Estimated position

DR position

Dead reckoning

Dead reckoning![]() is a technique to determine a ship's approximate position by applying

to the last established charted position a vector or series of vectors

representing true courses and speed. This means that if we have an

earlier fix, we plot from that position our course and “distance

travelled since then” and deduce our current position.

is a technique to determine a ship's approximate position by applying

to the last established charted position a vector or series of vectors

representing true courses and speed. This means that if we have an

earlier fix, we plot from that position our course and “distance

travelled since then” and deduce our current position.

|

| |||||||||

Dead reckoning is crucial since it provides an

approximate position in the future. Each time a fix or running fix is

plotted, a vector representing the ordered course and speed originate

from it. The direction of this course

line represents the ship's course, and the length

represents the distance one would expect the ship to travel in a given

time. This extrapolation is used as a safety precaution: a predicted DR

position that will place the ship in water 1 metre deep should raise an

eyebrow…

In the example above the true courses are plotted in the

chart, and to assist the helmsman these course lines are labelled with

the corresponding compass courses.

Guidelines for dead

reckoning:

Plot a new course line from each new fix or running fix (single LOP).

Never draw a new course line from an EP.

Plot a DR position every time course or speed changes.

Plot a corrected DR position if the predicted course line proofed wrong, and continue from there.

Running fix

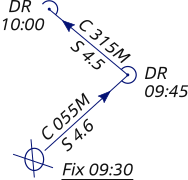

Under some circumstances, such as low visibility, only one line of position can be obtained at a time. In this event, a line of position obtained at an earlier time may be advanced to the time of the later LOP. These two LOPs should not be parallel to each other; remember that the optimal angular spread is 90°. The position obtained is termed a running fix because the ship has “run” a certain distance during the time interval between the two LOPs.

|

|

To use the LOP obtained at an earlier time, we must

advance it to the time of the second LOP. This is done by using the dead

reckoning plot. First, we measure the distance between the two DR

positions and draw a construction line,

which is parallel to a line connecting the two DR positions.

Note

that if there are no intervening course changes between the two DR

positions, it's easiest just to use the course line itself as the

construction line.

Now, using the parallel rulers we advance the

first LOP along this construction line over the distance we measured. Et

voilá, the intersection is our RFix.

If there is an intervening

course change, it appears to make our problem harder. Not so! The only

DR positions that matter are the two corresponding with the LOPs.

Guidelines

for advancing a LOP:

The distance: equal to the distance between the two corresponding DR positions.

The direction: equal to the direction between the two corresponding DR positions.

Draw the advanced LOP with a dotted line and mark with both times.

Label the Running Fix with an ellipse and "RFix" without underlining.

Danger bearing

Like the dead reckoning positioning, the danger bearing

is an important tool to keep the ship out of harm's way. First, the navigator identifies the limits of safe, navigable water and

determines a bearing to for instance a major light. This bearing is

marked as “No More Than” (NMT) or “No Less

Than” (NLT), depending on which side is safe.

Hatching is included on the side that is hazardous, along with its

compass bearing.

First, the navigator identifies the limits of safe, navigable water and

determines a bearing to for instance a major light. This bearing is

marked as “No More Than” (NMT) or “No Less

Than” (NLT), depending on which side is safe.

Hatching is included on the side that is hazardous, along with its

compass bearing.

In the example on the right a true course of 325° is

plotted (5° variation![]() ), marked with the magnetic

course of 320°, practical for a handheld compass that

requires no deviation correction.

), marked with the magnetic

course of 320°, practical for a handheld compass that

requires no deviation correction.

Were

we see that light at 350° magnetic - which is definitely “More Than” -

the rocks and wreck would be between us and the major light. A possible

cause could be a (tidal) stream from east to west.

When a distance![]() is used instead of a direction, a danger range is plotted much the same way

as the danger bearing.

is used instead of a direction, a danger range is plotted much the same way

as the danger bearing.

Turn bearing

The Turn bearing - like the

danger bearing - is

constructed in the chart in advance. It should be used as a means of

anticipation for sailing out of safe waters (again like the danger

bearing and dead reckoning). The turn bearing is taken on an appropriate

aid to navigation and is marked “TB”. As you

pass the object its bearing will slowly change. When it reaches the turn bearing turn the vessel on her new

course.

This type of bearing is also used for selecting an anchorage

position or diving position.

Snellius construction

Willebrord Snellius![]() - a 16th century mathematician from Leiden, the Netherlands - became

famous for inventing the loxodrome and his method of triangulation.

- a 16th century mathematician from Leiden, the Netherlands - became

famous for inventing the loxodrome and his method of triangulation.

The

Snellius construction was first

used to obtain the length of the meridian by measuring the distance

between two Dutch cities![]() .

He took angles from and to church towers of villages in between to

reach his objective. Nowadays we use the Snellius method to derive our

position from three bearings without the use of LOPs, and while leaving

out deviation and variation, which simplifies things. Also, since only

relative angles are needed a sextant can be used to measure navigation

aids at greater distances. Closer in a compass can be used.

.

He took angles from and to church towers of villages in between to

reach his objective. Nowadays we use the Snellius method to derive our

position from three bearings without the use of LOPs, and while leaving

out deviation and variation, which simplifies things. Also, since only

relative angles are needed a sextant can be used to measure navigation

aids at greater distances. Closer in a compass can be used.

The

construction:

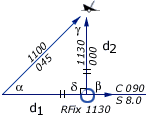

See figure 1: Compass bearings are 320° on A; 360° on B; 050° on object C.

The angle between A and B = 40°.

The angle between B and C = 50°.

Draw lines from A to B and from B to C.

Add the two light-blue perpendicular bisectors of lines AB and BC.

Draw at object A a construction line 40° inland of line AB.

Draw at object C a second construction line 50° inland of line CB.

See figure 2: At object A: draw a line perpendicular to the construction line.

At object C: draw another line perpendicular to the construction line.

The two intersections with the light-blue lines indicate the centres of two circles.

Finally, draw the first circle using A and B and the second circle using B and C.

The off shore intersection of the two circle gives us our position fix.

The advantage: deviation and variation can be left out since the angles (here 40° and 50°) are relative ones. Moreover, a sextant can be used to obtain angles between objects at greater distances, that with a compass would be less precise.

International notation

| International notation conventions for plotting in the chart | ||||||

| Fix | LOP | |||||

| Running Fix | LOP advanced | |||||

| Estimated Position | Course & Speed | |||||

| Dead Reckoning | Set & Drift | |||||

| Electronic Fix (GPS) | ||||||

| Electronic Fix (Radar) | ||||||

Note, that a few countries use an alternative symbol ![]()

Plotting should be done with a soft pencil. Moreover, avoid drawing lines through the chart symbols. This is to prevent damage to the chart when you have to erase the construction.

Learn sailing and navigation via yacht charters with instruction in Greece.

Glossary

Line Of Position (LOP): The locus of points along which a ship's position must lie. A minimum of two LOPs are necessary to establish a fix. It is standard practice to use at least three LOPs when obtaining a fix, to guard against the possibility of and, in some cases, remove ambiguity.

Transit fix: The method of lining up charted objects to obtain an LOP.

Leading lights or Range lights: A pair of lights or day marks deliberately placed to mark a narrow channel.

Position fix: The intersection of various LOPs.

Cross bearing: The use of LOPs of several navigational aids to obtain a position fix. Remember to use an optimal angular spread.

Running fix: The use of an advanced LOP. Make sure to use only the corresponding DR positions. Also don't use the EP for advancing the first LOP.

Dead reckoning: Determining a position by plotting courses and speeds from a known position. It is also used to predict when lights become visible or to determine the set and rate of a current.

Estimated position: Combine a corresponding DR position with a single LOP to get an EP position.

Snellius construction: Another way to combine three compass bearings to obtain a position fix. The advantage over a cross bearing is that both magnetic variation and deviation don't need to be taken into account.

Course: (C) The

direction in which a vessel is steered or is intended to be steered

(direction through the water). Course to

steer: Course to steer to counteract current and leeway

[bovenstroomse koers]. Heading (HDG):

The direction in which the boat is pointing in any instant

[voorliggende koers].

Heading (HDG):

The direction in which the boat is pointing in any instant

[voorliggende koers].  Course To Make Good

(CTMG): The course for planning purposes that indicates the

intended track from departure to destination.

Course To Make Good

(CTMG): The course for planning purposes that indicates the

intended track from departure to destination.

Course Made Good (CMG): The single resultant direction from the point of departure to the point of arrival at any given time. Course line Construction line Danger range -->

Speed: (S) The

speed of the boat through the water. Speed

Made Good (SMG): The speed of the boat achieved over the CMG

line.

-->

Set: (SET) The direction in which the current is flowing (see chapters 6,7 and 8).

Drift: (DFT) The speed (in knots) of the current (see chapters 6,7 and 8).

Default heading is True course (M = magnetic , C = compass).

Default time is 24 hour clock ship time else UTC.

Piloting and

navigation

Home Nav.

course Sailing Greece

Turkish Coasts

Yacht

charter Gulets

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Doubled angle fix

The Doubled angle on the bow fix resembles a running fix though only one navigation aid is used.

|

| α = 30° , β = 60° δ = 120° , γ = 30° Isosceles d1 = d2 |

In the example on the right the initial angle (30°) on

the bow is doubled (60°) yielding an isosceles triangle![]() . The distance travelled between the bearings is the same as

the distance from the visible wreck.

. The distance travelled between the bearings is the same as

the distance from the visible wreck.

Start with the visible wreck having a bearing of less than 45° off the bow (α), note the log distance.

Proceed along the course until the angle on the bow is doubled (β), read the log: d1 is 10 nm.

Use the log distance to find the position on the second LOP. It is an isosceles triangle, so d2 is also 10 nm.

Label it with an ellipse and "RFix" but realize it is less precise than a running fix that involves two navigation aids.

Four point fix

If the first angle on the bow is 45°, a special

situation occurs: The Four point fix,

so called since 45 degrees equals 4 points on the compass (1 point =

11,25°![]() ).

).

|

| α = 45° , β = 90° δ = 90° , γ = 45° Isosceles d1 = d2 |

Start with a bearing with 45° on the bow (α), note the log.

Proceed along the course till the angle on the bow is 90° (β), read the log: d1 is 4 nm

Use the log distance to find the position on the second LOP. Isosceles, so d2 is also 4 nm.

Label it with an ellipse and "RFix".

Special angle fix

The Special angle fix

requires the mariner to know some special pairs of angles (a : b) that give

the distance travelled between bearings as equal to the distance abeam![]() .

.

|

| α = 21° , β = 32° d1 = d2 |

In the example on the right α =

21° and β = 32° are used. Now,

the log distance equals the shortest distance between wreck and course

line (6 nm).

A few practical pairs:

16 : 22 21 : 32

25 : 41 32 : 59

37

: 72 40 : 79

Remember: the greater the angular spread the better.

Hence, of these three fixes the four point fix is the most precise one.

Mathematics: isosceles triangle fixes

Distance of the horizon

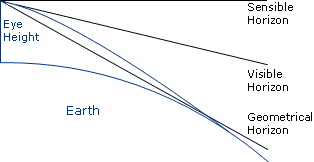

On a flat world there would be no difference between the

visible and sensible horizon. However, on Earth the visible horizon appears several arc

minutes below the sensible horizon

due to two opposing effects:

the curvature of the earth's surface;

atmospheric refraction.

Atmospheric refraction bends light rays passing along

the earth's surface toward the earth. Therefore, the geometrical horizon![]() appears elevated, forming the visible horizon.

appears elevated, forming the visible horizon.

The

distance of the visible horizon is a (semi-empirical) function of Eye

Height:

![]()

![]()

Mathematics: horizon distances

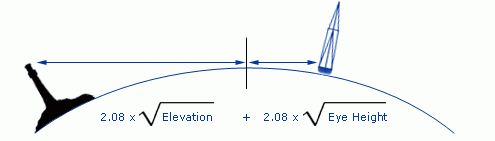

Dipping range

If an object is observed to be just rising above or just

dipping below the visible horizon, its distance can be readily

calculated using a simple formula. ![]() The object's elevation (the

height of a light above chart datum

The object's elevation (the

height of a light above chart datum![]() )

can be found in the chart or other nautical publication such as the

'List of Lights'. Note that in some charts elevation is referred to a

different datum than soundings

)

can be found in the chart or other nautical publication such as the

'List of Lights'. Note that in some charts elevation is referred to a

different datum than soundings![]() . Click on the image on the right to view a magnificent

lighthouse.

. Click on the image on the right to view a magnificent

lighthouse.

The formula contains the two distances from the visible

horizon and can be simplified by the equation: 2.08 x (√Elevation + √Eye

height)![]() . Many nautical publications contain a table

called "distances of the horizon" which can be used instead of the

equation.

. Many nautical publications contain a table

called "distances of the horizon" which can be used instead of the

equation.

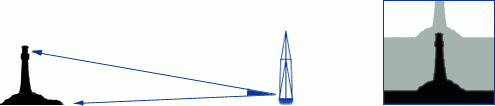

Use the dipping range to plot a Distance LOP![]() in the chart: a circle equal in radius to the measured distance, which

is plotted about the navigation aid. Finally, take a bearing on the

object to get a second LOP and a position fix.

in the chart: a circle equal in radius to the measured distance, which

is plotted about the navigation aid. Finally, take a bearing on the

object to get a second LOP and a position fix.

Vertical sextant angle

Similarly, a distance LOP can be obtained by using a

sextant to measure the angle (arc) between for instance the light![]() and chart datum of a lighthouse or any other structure of

known elevation. Once the angle is corrected for index error the distance can be found in a

table called: "Distances by Vertical Sextant Angle", which is based on

the following equation.

and chart datum of a lighthouse or any other structure of

known elevation. Once the angle is corrected for index error the distance can be found in a

table called: "Distances by Vertical Sextant Angle", which is based on

the following equation.

![]()

![]()

The angle in minutes total, thus 1° 12' = 72' total, and corrected for index error.

Elevation in metres![]() .

.

Water height in metres above or below chart datum of object.

Distance or Range in nautical miles.

Ascertain whether the base of the object is beyond the horizon

Corrected angle should be greater than 20'.

Though tables can be used for quick reference, this

function is valid for objects higher than usually tabulated![]() . An example with a lighthouse of 80 metres:

. An example with a lighthouse of 80 metres:

Measured angle is 1° 19', index error is +6': angle = 73'.

Let's assume water height at 3 metres above Mean Level datum.

Range = 1.854*(80-3/73) = 1.96 nm.

The range can be used as a danger bearing.

Together

with a compass bearing one object with known elevation results in a

position fix. If more than one vertical sextant angle is combined the

optimum angular spread should be maintained.

Often, the correction for water height

can be left out. Though, realizing that the horizon is closer than one

might think![]() ,

another correction is sometimes needed. In the Mediterranean Sea for

example we can see mountain tops with bases lying well beyond the

horizon. Mutatis mutandis, the structures, which they bear have bases

beyond the horizon as well.

,

another correction is sometimes needed. In the Mediterranean Sea for

example we can see mountain tops with bases lying well beyond the

horizon. Mutatis mutandis, the structures, which they bear have bases

beyond the horizon as well.

![]()

![]()

This is the equation for finding the distance of an object of known elevation located beyond the horizon. In the denominator of this equation a compensating factor is included by which the measured angle should be reduced.

Mathematics: vertical sextant angles

Estimation of distance

The most obvious way to estimate distances is of course

by using the distance between our eyes.  If we sight over our thumb first with one eye then with the other, the

thumb moves across the background, perhaps first crossing a tower second

crossing a bridge.

If we sight over our thumb first with one eye then with the other, the

thumb moves across the background, perhaps first crossing a tower second

crossing a bridge.

The chart might tell that these structures are 300 m

apart.

Use the ratio of: distance between eye and outstretched

arm/distance between pupils: usually 10![]() .

.

The objects are 3 kilometres away.

Other

physical relationships are useful for quick reference. For example, one

finger width held at arm's length covers about 2° arc, measured

horizontally or vertically.

Two fingers cover 4°. Three fingers cover

6° and give rise to the three finger rule:

"An

object that is three fingers high is about 10 times as far away as it

is high."

Estimation with horizon

The image on the right shows us that it is possible to estimate the height of any object that crosses the horizon as seen from our own point of view.

|

This picture of the 'Pigeon Rocks' near Beirut harbour

was taken from a crow's nest at a height of 34 metres.

The distance

of the visible horizon (12 nm) is far larger than 34 metres![]() . Therefore, we can - without any other information -

estimate that these rocks have a height of 34 metres as well.

. Therefore, we can - without any other information -

estimate that these rocks have a height of 34 metres as well.

Factum: All tops crossing the horizon

and with bases at sea level are on eye level![]() .

.

Furthermore, if we see these rocks over a vertical angle

of for example 7°![]() = 0.1225 rad., then the range is

34/0.1225 = 277 metres.

= 0.1225 rad., then the range is

34/0.1225 = 277 metres.

Finally, plot both range and bearing in the

chart to construct an EP, et Voilà!

Fix by depth soundings

A series of depth soundings - in this example every 10 minutes - can greatly improve your position fix:

correct your soundings for tide, etc.![]() ;

;

copy the DR course line on a transparent sheet;

write the depths adjacent according to the times of the soundings;

move the sheet over the chart to find its best location.

Due to leeway, currents or other factors the two course lines need not be parallel to or of same length as each other.

Yacht charters and

learning how to sail in Greece with instruction.

Overview

Line Of Position (LOP): The locus of points along which a ship's position must lie. A minimum of two LOP's are necessary to establish a fix. It is standard practice to use at least three LOP's when obtaining a fix, to guard against the possibility of and, in some cases, remove ambiguity.

Range or Distance LOP: Obtained by using a stadimeter, sextant or radar. A circle equal in radius to the measured distance is plotted about the navigation aid; the ship must be somewhere on this circle.

Running fix: A position determined by crossing lines of position obtained at different times and advanced or retired to a common time.

Dead reckoning: Determining a position by plotting courses and speeds from a known position. It is also used to predict when lights become visible or to determine the set and drift of a current. DR positions are drawn in advance to prevent sailing into danger. A DR position will be plotted:

-

every hour on the hour;

-

at the time of every course change or speed change;

-

for the time at which a (running) fix is obtained, also a new course line will be plotted;

-

for the time at which a single LOP is obtained;

-

and never draw a new course line from an EP position!

Estimated position: The most probable position of a craft determined from incomplete data or data of questionable accuracy. Such a position might be determined by applying a correction to the dead reckoning position, as for estimated current; by plotting a line of soundings; or by plotting a LOP of questionable accuracy.

Double angle on the bow: A method of obtaining a running fix by measuring the distance a vessel travels on a steady course while the relative bearing (right or left) of a fixed object doubles. The distance from the object at the time of the second bearing is equal to the run between bearings, neglecting drift.

Four point fix: A special case of doubling the angle on the bow, in which the first bearing is 45° right or left of the bow. Due to angular spread this is the most precise isosceles fix.

Special angle fix: A construction using special pairs of relative angles that give the distance travelled between bearings as equal to the navigation aids' range abeam.

Distance from horizon: The distance measured along the line of sight from a position above the surface of the earth to the visible horizon.

Sensible horizon: The circle of the celestial sphere formed by the intersection of the celestial sphere and a plane through the eye of the observer, and perpendicular to the zenith-nadir line.

Visible horizon: The line where Earth and sky appear to meet. If there were no terrestrial refraction, visible and geometrical horizons would coincide. Also called : apparent horizon.

Geometrical horizon: Originally, the celestial horizon; now more commonly the intersection of the celestial sphere and an infinite number of straight lines tangent to the earth's surface and radiating from the eye of the observer.

Dipping range or Geographic range: The maximum distance at which the curvature of the earth and terrestrial refraction permit an aid to navigation to be seen from a particular height of eye (without regard to the luminous intensity of the light).

Elevation: The height of the light above its chart datum in contrast to the height of the structure itself.

Chart Datum: Officially: Chart Sounding Datum: An arbitrary reference plane to which both heights of tides and water depths are expressed on a chart. In the same chart heights can be related to other datums than depths.

Vertical sextant angle: The method of using the subtended angle of a vertical object to find its range.

Index error: In a marine sextant the index error is primarily due to lack of parallelism of the index mirror and the horizon glass at zero reading. A positive index error is subtracted and a negative index error is added.

Estimation with horizon: Estimation of heights using the horizon: All tops crossing the horizon and with bases at sea level are on eye level.

Estimation with depth effect: .

Estimated position with soundings: